How to set up your CI/CD pipeline for faster feedback

One of the biggest issues that plagues teams doing some form of Continuous Integration / Delivery / Deployment is execution time. If the pipeline is slow, then the feedback loop is slow.

If the code takes 30 minutes to pass through the pipeline and build only to fail in UAT or even worse, production, precious time is wasted (and money).

Going fast is not only about shipping fast but also about failing fast. The faster you fail, the cheaper the solution.

Then there’s the endless war about Monoliths vs. Microservices which is also holding your team back from focusing on work and delivering properly.

If you’re looking for a design that would facilitate tightening the feedback loop, read on, it might prove to be the last article you will need to read, to solve this problem.

The slow pipeline

Let’s assume we have a team practice continuous integration (CI) for 6 months. The next step would be to implement a continuous delivery (CD) pipeline. This means automating the build process as well as storing the results of successful builds. The team can later deploy the resulting artefacts at the push of a button.

The structure of the CI workflow is as follows: code quality → unit tests

In the past 6 months, the team also focused heavily on writing end-to-end tests and run them locally using Selenium.

For almost every new feature added to the application, they also have an end-to-end test written. This way, whenever someone changes the user interface, the system will be able to catch the differences and signal the team about any issues. They’re still not integrated in the main pipeline. The plan is to merge them in to gain more confidence in what they build. The tests should run whenever anyone pushes changes to the git repository.

Work starts on the new CD pipeline and everything is set up accordingly. The pipeline structure looks like below:

code quality → unit tests → build → staging deployment → e2e test

For every developer pushing code to the repo, the system kicks off a process and runs the whole pipeline.

What is slow here? It’s the E2E test suite, of course!

Running it at every code push is costly, not only in terms of resource utilization (machines, networks, servers) but also in terms of developer time. Whenever the build breaks, all work should stop and the build should be fixed before introducing more features (and possibly more problems). The developer has to wait for the build to pass in order to move on.

Imagine there are 2 or more developers working on that branch. They would have to push to version control only when they are sure the functionality is 100% ready. This leads to more problems. I remember when we used to work with SVN and we could only push when the feature was ready. Otherwise, we would break the application for every person working on the project.

Types of tests

In my experience, teams aspiring to implement Continuous Delivery always had to implement at least the categories of tests outlined below. For a more in-depth list of tests, check out the resources section at the end of the article.

Unit tests

These tests are the fastest and also the most important. They provide fast feedback about the correctness of the code. If everything is green at this step, it means that your code is sound. Note that it doesn’t mean it won’t fail once it reaches production.

No project can do CD without a proper CI pipeline. The two pillars of CI pipelines are tests and code quality(standardization). Without coding standars, a static code analysis tool to automate the validation process and a lot of unit tests, you can’t even plan to implement Continuous Delivery.

Integration tests

These usually fall into 2 categories.

When talking about modules of the same application, the integration tests make sure that the new module being added, plays well with the already existing modules.

The second category are the inter-service tests. In a microservices architecture you need to make sure that the updates you perform to one service, don’t mess everything up for the other services.

End-to-end tests

Although it can be done with microservices as well, end-to-end testing is very popular today with front-end applications. These tests assess that a specific workflow in your application, can be carried out successfully, without errors, under the conditions described by the specs.

A good end-to-end testing framework will allow you a bare minimum of interactions, outlined below:

- Open the application in a browser

- Interact with the application (click buttons and links)

- Fill and submit forms (add strings to input fields, manipulating select boxes, checkboxes, etc.)

- Validate if certain areas of the page are present

- Validate if areas of the page are visible or invisible

This category of tests are the biggest confidence boosters. If these tests pass, you have a 95% chance for everything to be fine in production, too.

The problem is that people tend to overdo these tests. Because they are highly visual, managers love them, QA people love them (it was their previous job), everyone loves them. Except when have an E2E test for every button click. If QA pick up on the skills to write the tests themselves (and they should), they will tend to automate everything they can click on. This becomes a pain because you might not want to run the login screen test 15 times, just so you can perform different actions in the application.

Load/stress tests

In the case of an SLA(Service Level Agreement) terms such as latency, response time and uptime may be required. In this situation, the code has to pass unit tests, integrate well with the rest of the functionalities and behave well with other parts of the larger system but it should do all of these in a performant way.

This is where load and stress tests come in. They enable us to validate the boundaries to which the application behaves normally.

They offer a pretty clear view how the application will behave in production, under a specific load. This helps a lot with resource dimensioning, the number of application instances to have up under regular traffic conditions and a lot more. They can also provide a decent baseline for performance improvement actions, during a project’s lifecycle.

Order and discipline

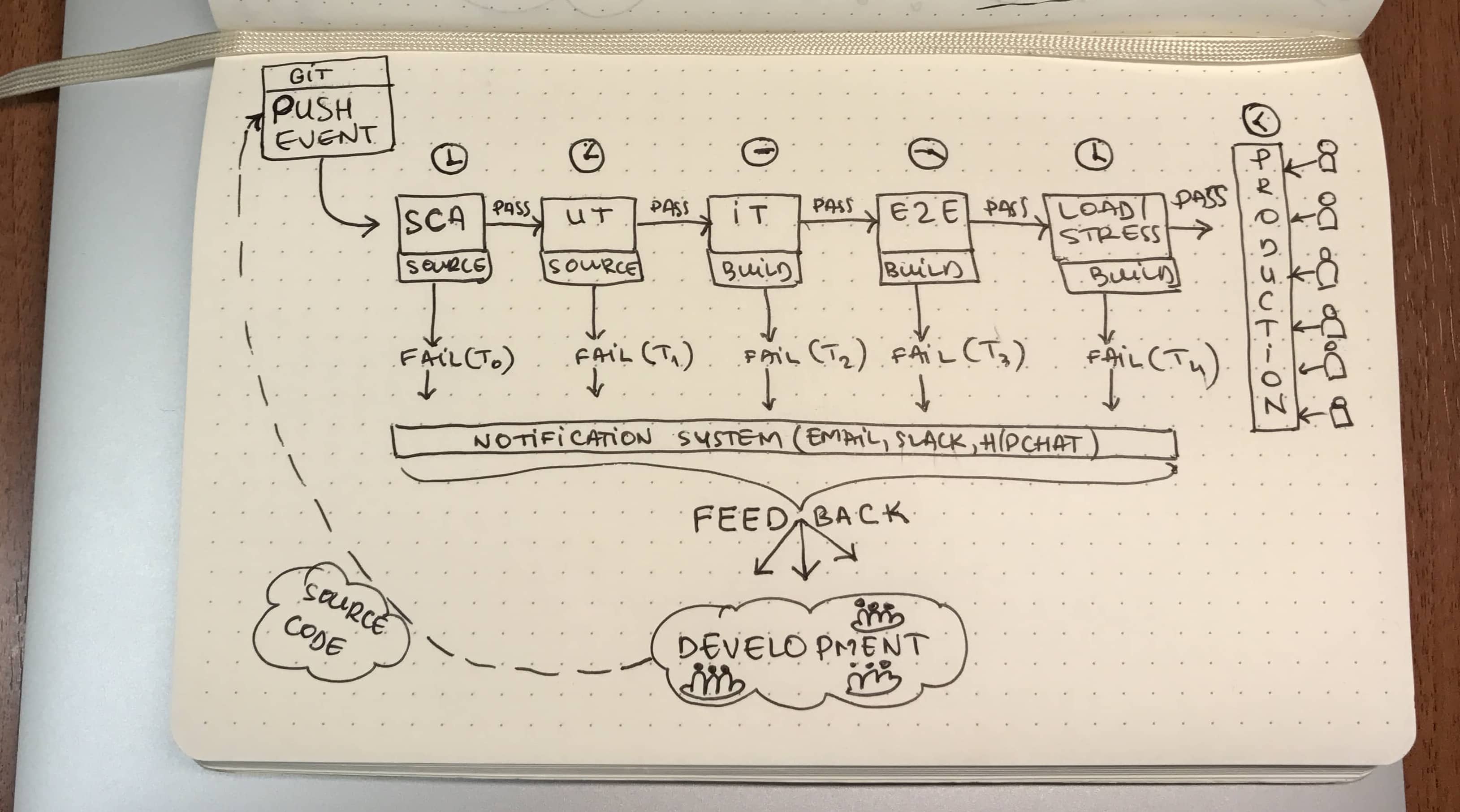

Now that we know what each of the general testing strategies we have at our disposal, let’s see how would a continuous delivery pipeline look. The order we are looking for is provided by the sequence in the image below.

Let’s go through the steps in sequence:

1. SCA — Static Code Analysis

If we have coding standards in place, and we should, this is the first thing we need to run. We don’t need to create a build, or do anything of that nature. We only need to pass through our code and see if we introduced any syntactic errors.

If this step is fine, this means that our code adheres 100% to our style guide. You may have some rules in your style guide that you break intentionally. Configure the linter to issue a warning instead of an error. Whatever you do, don’t disable them! You might want to revise the code 1 year from now and you won’t know what’s happening there.

2. UT — Unit Tests

Like we discussed previously, there’s no CD without CI. Continuous Integration is at the root of every automation process that involves delivery or deployment. Make sure they run fast. You don’t want to wait 15 minutes to get feedback after running an UT suite. Better yet, you should be able to run the full suite on your development machine near real-time.

3. IT — Integration Tests

Make sure you know if there’s anything wrong with the functionality you developed, by now. At this stage, you find out if features the team developed get along. For this to work properly, you need a separate environment. If you’re a startup and don’t have much to invest in 10 separate environments, you can use UAT (Staging).

There are tests that assess if and how modules get along with each other. These can run as a separate suite, with the service started in isolation. If you run microservices, the inter-service tests need to be performed while running the services on an environment such as UAT.

4. E2E — End-to-End Tests

After making sure the components integrate well, we run a series of tests that describe user flows. A user flow is the series of steps a user needs to take to accomplish a specific task. For example, if a user wants to update their profile picture, a E2E test for this would have the following steps:

- Open login page

- Fill username and password. Submit form

- Open profile page

- Click “Edit”

- Click “Change profile image”

- Fill image path. Click “Upload”

- Validate the image has changed

All the steps above also contain validations. For example, you want to validate that the user is logged in after you submit the login form. You might have a test that validates if the “Logout” button is present in the DOM and is visible.

E2E tests usually take longer to run and offer feedback so you want to have them running later in the process. You also don’t want to have too many of these tests. Try to capture most of the issues outlined by E2E tests in your unit tests. This way, you will have fast feedback and you will increase your confidence in the test harness.

They also tend to be flaky. I’ve worked with Selenium based E2E testing tools and it has a tendency to be a bit inconsistent. One strategy I picked up from a blog post I can’t remember right now is to have a specific failure tolerance for E2E tests. For example, you run the E2E suite three times. If it fails all three times, you then alert the developer / team about the issue.

A node might fail, or worse, it might hang. This is not necessarily a problem with your application or tests, but still, your tests will fail. You need to have a mechanism in place to kick the process off a couple of times and observe the behavior.

Be aware that once they see E2E tests, business will ask more and more of these. For them, this type of visual tests are more reassuring. Being humans, we’re all prone to the WYSIATI bias — What You See Is All There Is. To find out more about this bias, read Daniel Kahneman’s outstanding book, Thinking Fast And Slow.

5. L/ST — Load/Stress Tests

As described earlier, Load/Stress Tests come into play whenever you have service quality constraints. This doesn’t mean that you need a contract for that. This is only one case. You can also set internal standards that you treat as contracts. I have three reasons for using this type of testing:

- To measure the quality of my service and compare it with a baseline.

- To establish or push the baseline by benchmarking the application after a major technical decision has been implemented, refactoring work and so on.

- To be able to perform a responsible resource dimensioning. Using real-life application metrics and the ones resulting from load/stress tests teams can make more informed decisions about the number of machines, CPUs, amount of RAM to use for a certain software application ecosystem.

With the right amount of tooling, you are able to properly assess how your application will behave under a specific load. This, along with the metrics you collect while your application is running in production, will give you a clear view of how and when to scale and up to what point.

Environments

Not everyone owns a datacenter; nor do they need to. With the rise of companies such as Amazon, Microsoft, Digital Ocean or Linode in the cloud “industry” most of the businesses I’ve worked with would be insane to self-host their applications.

I do agree that you don’t want to go wild with environments. For a good separation of responsibilities, you need at least two environments except development and production: BUILD and UAT.

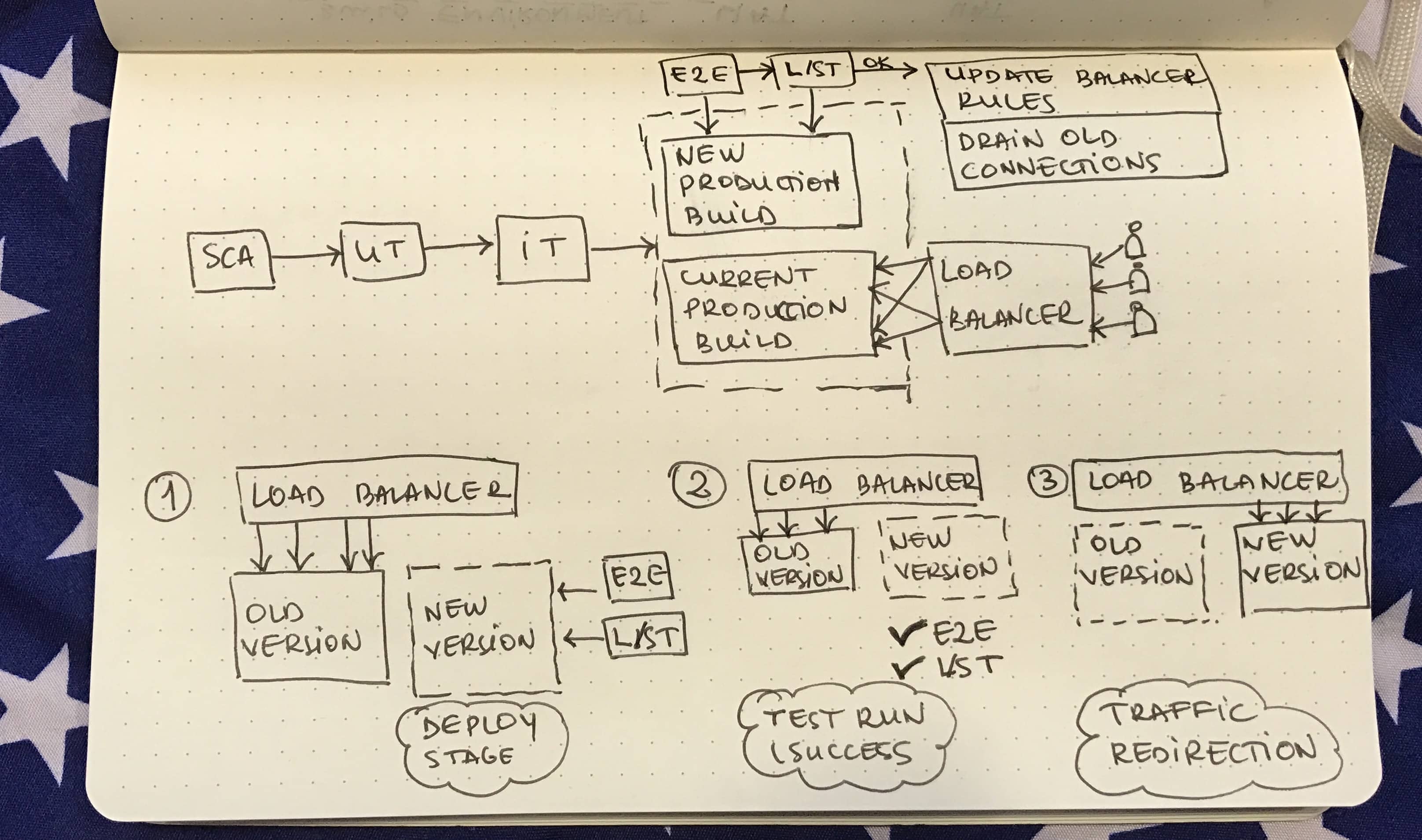

Take a look at the flow diagram below. I placed each step of the pipeline in its respective environment. See how E2E and L/ST can also run in UAT and PROD? The mix of tests that run in production are called Smoke Tests. These tests are a mix between End-to-End, Load/Stress Tests and a bit of manual tests (hopefully a very small bit).

You want to validate that whatever you are pushing into production doesn’t just “pass” the tests but that it also passes the human interaction phase. If there’s no difference between your environment configuration — UAT vs. PROD — you shouldn’t have anything to worry about.

Extras

You might ask: “How can I run E2E and L/S T in production? Wouldn’t that affect the currently active users?”. You’re right, there’s actually a technique for that. You don’t release into production, you just deploy the application. Take a look at the image below to get a better view on the technique.

You just push your build into production but you don’t direct traffic to the appilcation. You can then run the proper test suites on that build, directly in production. Once everything passes, you are free to update the load balancer rules and direct traffic to the new version of your app.

You just push your build into production but you don’t direct traffic to the appilcation. You can then run the proper test suites on that build, directly in production. Once everything passes, you are free to update the load balancer rules and direct traffic to the new version of your app.

Unit tests can also be optimised to fail faster. Remember, we are optimizing for faster feedback. Failure falls into that category.

You can have different suites of tests running in parallel. This way, if any of the suites fails, everything fails. You don’t have to wait for them to run in sequence. Take a look at the updated flow diagram below.

You can do the same with E2E tests, as well. If you have your flows separated properly, there’s no reason for you not to run everything in parallel.

Putting it all together

It is very important to know that we should refrain from optimizing for the best case. It is always better to optimize for failure, expect it, embrace it.

Feedback is very important but if it comes slow, or after you pushed to production, it has no preventative value. It only serves as a lesson learned. Having feedback from the early beginnings of a project, and receiving it fast, is the cornerstone to Continuous Delivery / Deployment. It allows you to optimize ahead of time, with little to no impact on your users. It is better to delay a feature release for two days, than to deploy a non-working version.

Resources

- Martin Fowler - TestPyramid

- Introducing the software testing ice-cream cone (anti-pattern)

- Introducing the Software Testing Cupcake (Anti-Pattern)

- Wikipedia - Software Testing - Testing Types

- Software Testing Help - Types of software Testing

Photo credits: Dirk Haun — I Broke The Build